A report on the 2014 Proa Raid in Poland

We are a group of friends sailing proas from Poland and Germany. Every year we meet to share our experience and to raid together to gain some more experience. Last year we were sailing on the Baltic Sea. We had the same idea this year, after the Proa Conference at Jamno Lake in Poland. But we had to change our plans. The channel between the lake and sea was closed, what we had discovered in the last hours before start. We couldn’t get boats to the seashore, across forest and dunes - big frustration. We packed our boats and hit the road, changing the spot. So this year we started near Gdańsk, the biggest Polish city on the coast.

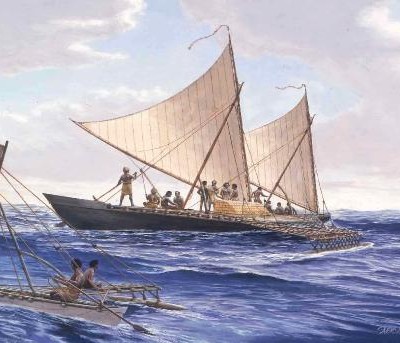

Three boats attended Proa Raid 2014. All of them were shunting proas with crab claw sails. Strictly shunting, no tacking, no safety gear to protect the fail of the mast in a back-wind. No motor.

1. Mata Pjoa. The best and biggest Polish proa. Designed by Janusz Ostrowski. LOA 7m, LWL 6,2m, sail 16,6 m2 from polytarp 140 g (the third year in use). Hulls build from plywood 4mm, pine frames, ama 2/3 of vaka displacement 120 liters, 25 kg, width from axis to axis ½ length of vaka. Vaka is asymmetric deep “V” with semi-spherical sides. All spars, except the mast, are made from hollow pine, including iakos. Worth to mention it is first grade pine. Joining of vaka and ama is flexible, ama can to move independently to a great extent. Toliwaga: Janusz, crew: Mateusz and sometimes myself (Grzegorz Korczynski).

2. Lili`Uokalani. Follows Otmar Karschulin’s P5 design with improvements by Reto. Built by Reto Brehm, Bavaria, Germany. LOA 5m, the rest of P5 data available on internet. Vaka and ama build from 4mm plywood, all spars – carbon fiber. Sail – dacron, the biggest possible. A real “hot-rod” proa. Toliwaga: Reto, crew: Erika (me the first day, when Erica was checking how Mata Pjoa behaves on a chop of Zatoka Gdańska)

3. Basso. Designed and built by Paweł Kowalski from Poland. LOA 4,6m, LWL 4,3 m. Ama displacement 47 kg. Width from axis to axis 2,2 m. Vaka and ama made from 4 mm ABS with aluminum stripes on the edges. Glued and melted. Spars made from aluminum. Sail 10 m2 from polytarp 140g. Mast 4m long. The white boat on the pictures. Toliwaga: Paweł. Crew: myself, starting from the second day.

The Raid

Day 1 - Tuesday, 8th of July 2014

We came by Wisła Śmiała (old estuary of Vistula river) to the sea, and sailed against the east wind. This day the wind was NE, about 3B, the sea 2B. We sailed by the sea towards actual Wisła River estuary. But little drama has happened to Basso. We had to land on the beach for a rescue operation – ama of Basso was full of water. Paweł this day was sailing alone on Basso. Basso behaves very well but with ama full of water she is hardly predictable, or sometimes absolutely unable to go off-wind. Basso was fallen aside by a squall (the only capsize we had during all raid) but Paweł straightened Basso back and almost stayed dry!!! I have no idea how he could do that. In the entrance to the harbor of Wisła Śmiała, when we come back from the sea, Basso was back winded and again Paweł managed to get all things streamlined and finished without any help.

Three proas have passed by sailors and windsurfers from Polish National Center of Sailing in Górki Zachodnie, impressing them with speed and rare view of full crab claw sail set off-wind. We came back to our camping place on the bank of the river, a man was waiting for us at our camp, he demanded an explanation of what kind of boats we are sailing. So Janusz and I as a crew offered him a short evening sailing in relaxing 1-2B wind. I would say it was perfect, effortless sailing and the crew (me) had nothing to do at all. His name was Lech and he was very enthusiastic. Being a former sailor and the man of the sea (working his whole life as an officer on big fishing boats from Poland to Argentina) he felt absolutely boat-less and aborted after this evening sailing. When we came back some days later we realized that meanwhile he had bought a used 420 class sailing dinghy. Firstly he wanted to build a proa, but during sailing on Mata Pjoa he realized, that proa is rather two person boat.

Day 2 - Wednesday 9th July 2014

Wind NE, in afternoon E-NE 3-4B, gusts 5B (more precisely in the morning 2B, from 11:00 3-4B, from 13:00 4-5B) Next days we had even more wind.

After packing our camp we had a discussion on where to go next. Weather forecast was indicating rather strong wind from the East. It meant that sailing to East on the sea, along the seashore, would be difficult, because of the waves which would appear soon, without a doubt. Going against a seaway with three boats of different length and construction would be disturbing, cause differences in speed.

We could go with the wind to the Zatoka Gdańska Gulf, but the place during holidays is very crowded. A lot of loud disco music and motorboats – not even close to our taste…

Third solution looked a little crazy – go by the rivers against the wind to the Zalew Wiślany – a big lagoon on the East. We decided to choose the third option, although none of us used the proa on the river. OK – I did it once motoring Gary`s Waapa some years ago on the Bug River, but this time none of the boat had motor. Fortunately every one of us had a paddle.

We started our journey at midday, when the wind was really fresh or even stiff. Very soon we realized what Leszek said to us day before – a proa needs two pair of hands. I had to leave Mata Pjoa, where I was in the role of photo and notes taker and needed to join Paweł on Basso. Lucky me! Because for me the play and big time had started, for the readers of that story the opportunity to see pictures had ended. Anyhow – thank you strong wind!

Firstly we were not going straight against the wind and Martwa Wisła River is very wide. Sailing was quite interesting and we had the chance to learn how to prevent a capsize on Basso. We passed the pontoon bridge, having to wait a little for opening, which was too low even for a proa to pass beneath. After passing the bridge we started to paddle. It was very difficult to paddle against the wind.

After some time paddling Basso, Paweł and I had to stop, Basso was very difficult to operate again. Our first thought was right – ama was full of water again. Fortunately, by chance, we found a spot where fishermen were sometimes present. In the trash they left we found some empty plastic bottles. We packed the ama with as many plastic bottles as we could find and continued sailing.

We managed to come to a flood gate/canal lock. Shock and awe among passers-by as three proas want to travel the mouth of the Wisła River in a rather stiff wind. But OK – you want it – you will get it, please give us only 14 zlotys for every boat as a passing fee. We passed through the lock and came to the Wisła River. It is a very big river of the estuary, but this time, no paddling was required! Big, short waves (big for the river), they are coming from the sea. The wind was marvelous – very strong but not fully downwind. Being aboard the smallest proa, I felt absolutely safe and relaxed. For the two other proas – Mata Pjoa and Lily`Uokalani, sailing in Wisła was a peace of cake. For us in Basso it was also very tasty, but a rather well done steak, not a cake.

Soon enough, we saw the flood gates to the Szkarpawa River, joining Wisła with Zalew Wiślany Lagoon. After a short stop to bail water out of Basso’s ama (again full) we took our paddles and entered the gates. Passing through this 19th century construction was very interesting. The rule is the operator of the gates opens only one door for smaller vessels. We had to be rather careful, because our craft were obviously beamier than the average yacht. Our free space left was 10 inches on each side.

We entered Szkarpawa River, a small but very beautiful river with very clean water. Again we had to paddle against the strong wind, which was, I dare to say, not very comfortable. Fortunately we quickly found a very nice spot for camping, where the Kleszczewski family ran a little business, renting kayaks and some other boats in Żuławki village. They were so friendly we could hardly believe such hospitality. We erected our tents on their lawn with a fireplace and the shop was only half kilometer away. It’s obviously not true that we bought out all “Amber” beer in the shop, and took only the cold ones. Nor is it true is that I was eaten to the naked bones by mosquitoes, I survived just to write this story.

Paweł was seriously considering to end his raid at this camp, because of the sinking ama, but after some rest he decided to fix an issue and go with us. First attempt was with chewing gum. The second was better, with silicone. And he put two empty plastic bottles to the ama, just in case.

Day 3 - 10th of July 2014

After swimming in the river, eating breakfast, and visiting the historical house of the Maronites from 18th Century which the Kleszczewski Family is renovating at significant personal expense, we were on the river again. Against the strong wind again, so again, paddling.

We tried different configurations – first, three persons paddling on the biggest Mata Pjoa, two on Lily`Uokalani, one on Basso. Not a good idea, Basso was definitely too slow for the convoy.

Secondly we tried to tug Basso – 3 persons on Mata Pjoa, on Basso one man. A very bad idea, especially on the river. Every turn of Basso meant a stopping of Mata Pjoa. Deep ”“V” vaka is a powerful break if not following exactly in line first proa.

So finally we changed the configuration of the convoy back to the original – for every proa two persons. And during all this paddling Mateusz proved again to be the strongest paddler in our group.

Fortunately it was not too far to get to the turn of the river where the wind was not directed strictly against us. We started to sail to windward. Soon we realized that in our boats, without rudders and boards, we can use the whole width of the river, even going a little bit to the seagrass, not talking about kelp, when we could shunt.

Sailing on the river is a great training. You don’t want to lose ground because you know that the ultimate penalty is paddling again.

In Basso, the canoe was less comfortable for paddling (there is no cockpit, vaka is totally decked). Paweł and I decided not to paddle any more, even if the wing would come directly against us. Soon we were surprised that we could do it on the narrow river. the shunting proa with a crabclaw sail is a surprising boat.

Basso sailing against the wind was a little bit slower than other two boats paddling, but not slower dramatically. And for sure we had more fun. And less physical effort invested.

There were no people on the Szkarpawa River, only some kayaks, three motor yachts and one, ridiculously big power boat or rather a ferry. When she passed we had to escape to the sea-grass and wait until the river stopped moving. For all of us, it was impossible to imagine ourselves aboard that big boat.

We came to the bridge, and stopped for a while to find a restaurant for a dinner at last. The only restaurant for all the trip. We didn’t expect that we were going to such a wild part of Poland.

After a rather late dinner, we decided to set sail to avoid sleeping by the road traffic. The river was empty. The river banks were devoid of beach, full of only grass and trees. The twilight was coming. The first and only possible place to stop was in Tujsk, where we were allowed to camp at one farm by the river. It was a little bit embarrassing for us when the owner would not accept any money as a camping fee or reward. Erika had a nice chat with the lady owner of the property about gardening.

Day 4 - Friday, 11th July 2014

We started very early. Before 9AM we were in the canoes. Looking at the weather forecast, strong (4-5-6B ENE) wind, we had to change our plan again. The original idea to go to Zalew Wiślany Lagoon seemed not so good this day, because against the waves Basso would be slower than rest of the fleet. Decision was then to go with the wind, by the River Nogat to the medieval city Malbork. It meant a greater distance. So we sailed a little bit. Than stopped for breakfast on the proas. The weather was very nice, but the wind was strong and growing quickly.

In the strong wind, when we finally came to the corner of Zalew Wislany Lagoon, we got an important proa sailing lesson. We tried to change course and to turn to Nogat River. And: even if you KNOW what to do, when the wind is strong, and you suddenly get a very strong gust (even 6B I think), you start to forget what you should do.

We wanted to turn and change our course to sail offwind. We did it all – mast at the proper position, sail reduced by brailing lines, sheet taken, paddle operating on the proper side of vaka – and yet, we only achieved a very small change of direction of proa. At the last minute before sailing straight into the Zalew Wiślany Lagoon – illumination! Weight distribution! I just changed my sitting place and Basso immediately turned. In wind 4B my reactions were more or less automatic. In the gust 6B I was mesmerized. It was a very important lesson. And such a lesson must be learned by yourself. Because when sailing with our Resident Proa Guru Janusz Ostrowski, or with our Visiting Proa Guru Reto Brehm, everything is so smooth, that you start to think that sailing a deep ”“V” proa with a big crabclaw sail is ridiculously easy. It is not, it needs constant awareness and fast reactions.

Sailing Nogat River was a different experience. Sailing mostly downwind, when the wind is changing all the time as the river turns or you have big trees on the banks, you also need to be careful. Once we started to sail too fast and too close to the wind on Basso, we got backwinded. But this time our reactions were very fast, so we managed get her back to the right course. Another time we were taken by the strong gust to the sea-grass, also nothing worth mentioning if you are on shunting proa.

Eventually, some miles before Malbork, the ama of Basso was full of water again, and the buoyancy of empty bottles was obviously not sufficient. Paweł and myself were really tired, so the mistakes and errors were unavoidable and could become very serious. The only mature decision was to stop and end Basso’s journey.

Janusz had an idea to make a catamaran or tri from two proas (his big Mata Pjoa and smaller Basso), but geometrical problems occurred and the idea was rejected.

We hoisted the hull-vaka and outrigger-ama and all other parts of Basso up 10 meters to the road by the river bank. Paweł left his boat in the bushes and came to Gdańsk to get his car. That is another big asset of having a small proa – you can finish your trip almost everywhere.

The two proas – Mata Pjoa and Lili`Uokalani continued the raid. Fortunately Reto and Erika on Lili passed by Mata Pjoa, so they arrived first to the gates on the Nogat before 6PM, when it was closing for the day. Erika asked the two ladies who were in charge to wait 20 minutes for next proa. We were very surprised that Erika was successful, because she do not speak Polish and the ladies did not speak either German nor English. So she convinced them in German, thanks to her charm.

We passed through the gate. I was keeping the boat in the basin with my hands on the ladder. I remember a rather confused frog looking at me very suspiciously. The ladies in charge of the gates were also looking very carefully at the proas, certainly the first ones on Nogat River.

We traveled the rest of the Nogat River very comfortably, sailing all the time with only two or three shunts. by the evening we came to the gates in Malbork, of course too late to find someone there to negotiate the opening. We made a provisional camp, found some hotdogs at a nearby gas station and went to sleep.

Day 5 - Saturday, 12th July 2014

On Saturday the weather changed. Heavy rain and no wind… We resigned from packing the proas again and paddling to the camp ground in the center of the city of Malbork. Instead we came to the city, caught the train to Gdańsk, got our cars, came back, packed and that was the end of the raid.

And here I am, sitting and writing and trying to find some free time to go proa sailing again. What have we learned from our raid?

- Proas need two persons to sail. Of course in the light wind you can do it alone. But better to have two persons aboard

.

- For sailing in the sea it is better to have minimum 7 meters vaka. Well, the exception is when your name is Reto Brehm. We knew it before, just confirmation.

- The deep ”“V” proa and crabclaw sail are surprisingly good in sailing on the river, even upwind.

- Sailing on the river is not easy. The sentence ”“on the river the wind is always full down or straight up the river” is not true. The truth is that the wind likes to change direction on the river.

- Paddling against a strong wind we do not like. Paddling without the wind is OK.

- Outrigger-ama full of water dramatically changes sailing properties. Yet sailing with the ama full of water is still possible (proven), but rather challenging and uncomfortable.

- Sailing the proa with crabclaw sail gives more fun than on any other sailing boat. the proa is extremely versatile. I cannot imagine going to sea without an escort on any 5 meters unballasted dinghy in the wind 4-5B.

- If you want to camp in remote areas, like Nogat River, it would be good to have machete to cut grass.

- Holt hatches are unsatisfactory when mounted on a flexible working surface. Sinking and difficult to close or open (we knew it before, confirmed again). And obviously one shouldn’t keep them constantly under water.

More photos of the raid here.

— Grzegorz Korczynski for Proa File 07/2014

![Proa Raid 2014]()

For the past 100 years, Western sailing rig development has been in the hands of the sportsman. Sailing as a serious means of transport ended with the age of steam. Consequently, serious scientific study into sailing has been sporadic at best, and has largely depended on the vast amount of aerodynamic research done on behalf of the aeronautical industry.

For the past 100 years, Western sailing rig development has been in the hands of the sportsman. Sailing as a serious means of transport ended with the age of steam. Consequently, serious scientific study into sailing has been sporadic at best, and has largely depended on the vast amount of aerodynamic research done on behalf of the aeronautical industry.

Marchaj theorized that the crab claw develops lift in a different way than the standard Western Bermudan. It operates in what is called *vortex lift* mode, which creates powerful spinning tornadoes of air off the leading edge. The spinning vortexes are zones of intense low pressure, and thus lift is created. It is beyond the scope of this article go into the details of crab claw sail aerodynamics, but if you wish to learn more, Marchaj’ book

Marchaj theorized that the crab claw develops lift in a different way than the standard Western Bermudan. It operates in what is called *vortex lift* mode, which creates powerful spinning tornadoes of air off the leading edge. The spinning vortexes are zones of intense low pressure, and thus lift is created. It is beyond the scope of this article go into the details of crab claw sail aerodynamics, but if you wish to learn more, Marchaj’ book

Pioneered by Gary Dierking, the idea is to replace the back muscles of the crew with the contracting power of bungee cords. The mast must pivot fore and aft with the traditional Micronesian rig, and adjustable stays are the way it is done. If each stay has a length of bungee incorporated into it, then they will tend to keep the mast in the vertical position, yet will still allow the mast to be pulled down toward either end. As the mast tilts forward, the aft bungee stay stretches tight, which in effect creates stored energy, and when the forestay is released at the start of a shunt, the stretched backstay pulls the mast up to vertical, automatically.

Pioneered by Gary Dierking, the idea is to replace the back muscles of the crew with the contracting power of bungee cords. The mast must pivot fore and aft with the traditional Micronesian rig, and adjustable stays are the way it is done. If each stay has a length of bungee incorporated into it, then they will tend to keep the mast in the vertical position, yet will still allow the mast to be pulled down toward either end. As the mast tilts forward, the aft bungee stay stretches tight, which in effect creates stored energy, and when the forestay is released at the start of a shunt, the stretched backstay pulls the mast up to vertical, automatically. A novel rig developed experimentally by John Rowland. Its principle is similar to that of a skate sail where the skater passes the sail over his head in coming about. This radical approach to tacking a crab claw is being developed by several people at the moment. The scheme takes advantage of the ‘claws symmetry by placing a strut between the yard and boom, which are now interchangeable. The sail pivots over the mast, hinged to the mast head at the center of the strut. In a sense, the sail is "flown" over the top of the mast, much like a tethered hang glider, or Rogallo wing. In theory, if all sheets are let fly, the sail will assume a horizontal attitude and feather into the wind. Ironically, over-the-top coming about works best on boats that tack to come about, not shunt.

A novel rig developed experimentally by John Rowland. Its principle is similar to that of a skate sail where the skater passes the sail over his head in coming about. This radical approach to tacking a crab claw is being developed by several people at the moment. The scheme takes advantage of the ‘claws symmetry by placing a strut between the yard and boom, which are now interchangeable. The sail pivots over the mast, hinged to the mast head at the center of the strut. In a sense, the sail is "flown" over the top of the mast, much like a tethered hang glider, or Rogallo wing. In theory, if all sheets are let fly, the sail will assume a horizontal attitude and feather into the wind. Ironically, over-the-top coming about works best on boats that tack to come about, not shunt.

The Bolger proa rig echos the unique symmetry of the proa: the airflow reverses direction during a shunt, just like the water flow on the hull. The rig has many powerful advantages that have led to a 50-year series of attempts to develop it into a useful sailboat rig. It is a wonderful example of the maxim: "In theory, theory equals practice. In practice, it doesn’t." Though the rig has become known in proa circles as "The Bolger Rig" due to the fact that it was Bolger’s proa cartoon that became widely known, the rig in fact was invented in the 1960’s by members of the Amateur Yacht Research Society (AYRS) who thought so highly of its potential to christen it the "AYRS Sail".

The Bolger proa rig echos the unique symmetry of the proa: the airflow reverses direction during a shunt, just like the water flow on the hull. The rig has many powerful advantages that have led to a 50-year series of attempts to develop it into a useful sailboat rig. It is a wonderful example of the maxim: "In theory, theory equals practice. In practice, it doesn’t." Though the rig has become known in proa circles as "The Bolger Rig" due to the fact that it was Bolger’s proa cartoon that became widely known, the rig in fact was invented in the 1960’s by members of the Amateur Yacht Research Society (AYRS) who thought so highly of its potential to christen it the "AYRS Sail". Collapse in the upper third of the sail is caused by the actual line of rotation (red dotted line) being well aft of the theoretical line (blue). This puts the line of rotation aft of the lift line, and the upper third of the sail becomes over-balanced. »

Collapse in the upper third of the sail is caused by the actual line of rotation (red dotted line) being well aft of the theoretical line (blue). This puts the line of rotation aft of the lift line, and the upper third of the sail becomes over-balanced. » « When a dual halyard system is used, the actual line of rotation stays forward of the lift line, and the collapse does not occur.

« When a dual halyard system is used, the actual line of rotation stays forward of the lift line, and the collapse does not occur. Details of sail showing approximate positions of battens, reef cringles and straps, lazyjacks (red), parrels (blue). »

Details of sail showing approximate positions of battens, reef cringles and straps, lazyjacks (red), parrels (blue). »

Writer and naturalist Euell Gibbons was living in Hawaii and dining on the jungle flora and fauna in the 1950’s. He soon realized that "an island is a small body of land surrounded by the need for a boat", so he set out to build himself one. Euell had been a professional boatbuilder, so he knew something of what he was about.

Writer and naturalist Euell Gibbons was living in Hawaii and dining on the jungle flora and fauna in the 1950’s. He soon realized that "an island is a small body of land surrounded by the need for a boat", so he set out to build himself one. Euell had been a professional boatbuilder, so he knew something of what he was about. Being deep in Polynesia, Euell was naturally drawn to the native outrigger canoe. He had a good knowledge of the type, and spent a considerable amount of time studying museum models and local examples. Euell built a proa, patterned more on the classic Micronesian design than a Hawaiian canoe. He departed from tradition in some ways, first by building the canoe out of plywood (a very modern, high-tech material in those days) and then by taking liberties with the classic Oceanic rig. Euell wrote:

Being deep in Polynesia, Euell was naturally drawn to the native outrigger canoe. He had a good knowledge of the type, and spent a considerable amount of time studying museum models and local examples. Euell built a proa, patterned more on the classic Micronesian design than a Hawaiian canoe. He departed from tradition in some ways, first by building the canoe out of plywood (a very modern, high-tech material in those days) and then by taking liberties with the classic Oceanic rig. Euell wrote:

To make the 6 meter yard I joined two 3 meter sections of 50mm (2") bamboo with a dowel in the center and then wrapped it with fiberglass tape and epoxy. I also glued in smaller dowels at the small ends.

To make the 6 meter yard I joined two 3 meter sections of 50mm (2") bamboo with a dowel in the center and then wrapped it with fiberglass tape and epoxy. I also glued in smaller dowels at the small ends.